Tools for Translators

The "off-label" use of programs built for other purposes

Welcome to Extra Muros, a blog about matters of interest to self-directed learners. If you like what you see, please share Extra Muros with your friends. If you find Extra Muros tiresome, supercilious, or just plain wrong, please share it with your enemies.

Of late, I have been translating articles written by two writers - Ernst Jünger and Hugo von Freytag-Loringhoven - who liked to use words in unusual ways. In some cases, this was a matter of a word rarely encountered in the language in question. In others, the word in question appeared frequently in other texts, but with a somewhat different meaning.

In the course of moving paragraphs from one language to another, I made frequent use of my trusty old German-to-English dictionary. (How old is it? All I will say is that the venerable volume wears a school-style book cover that celebrates the bicentennial of the United States.) I also put a great deal of strain on the servers that host Google Translate.

There were instances, however, when neither of those tools, as splendid as they might be, were up to the job. One of these was the word Gehäftigkeit, which Google rendered as “vehemence” and the editors of my used-to-be-a-tree word book had declined to mention at all. As “vehemence” made no sense in the sentence in question, I resorted to the off-label use of programs built for other purposes.

I began with the advanced search page on the website of the Hathi Trust. This, which I often use to find books and articles, allowed me to search a collection of eighteen million or so digitized items for instances in which Gehäftigkeit appeared on a page. (The refined the search by limiting the results to appearances of the word that took place before 1913, the year of publication of the article I was translating.)

Of the sixteen books and periodicals that popped up on my screen, many struck me as highly polemic. While this tendency fit in nicely with the theme of “vehemence,” it seemed to be at odds with my desire for to find a secondary meaning. I thus choose the very last item that Hathi algorithm provided me, a “critical dictionary” published in 1889, less than a quarter-century before the time of the text in question.

With a degree of good fortune rare in the realm of research, this somewhat stochastic choice provided me with four alternative translations for Gehäftigkeit: hatefulness, odiousness, odium, and animosity. As each of these made sense within the context of the sentence in question, I could have ended my quest then and there. However, as I wished to showcase other resources of possible interest to translators, I plugged Gehäftigkeit into the Google Books Ngram Viewer.

The Ngram Viewer, which I have often used to explore the genesis of terms-of-art, took me to another dictionary of the Victorian persuasion. This compendium, which claimed descent from the grand glossary of the Brothers Grimm, provided me with a full quarter column of sentences, crafted by such worthies as Friedrich Schiller and Heinrich Heine, that featured Gehäftigkeit.

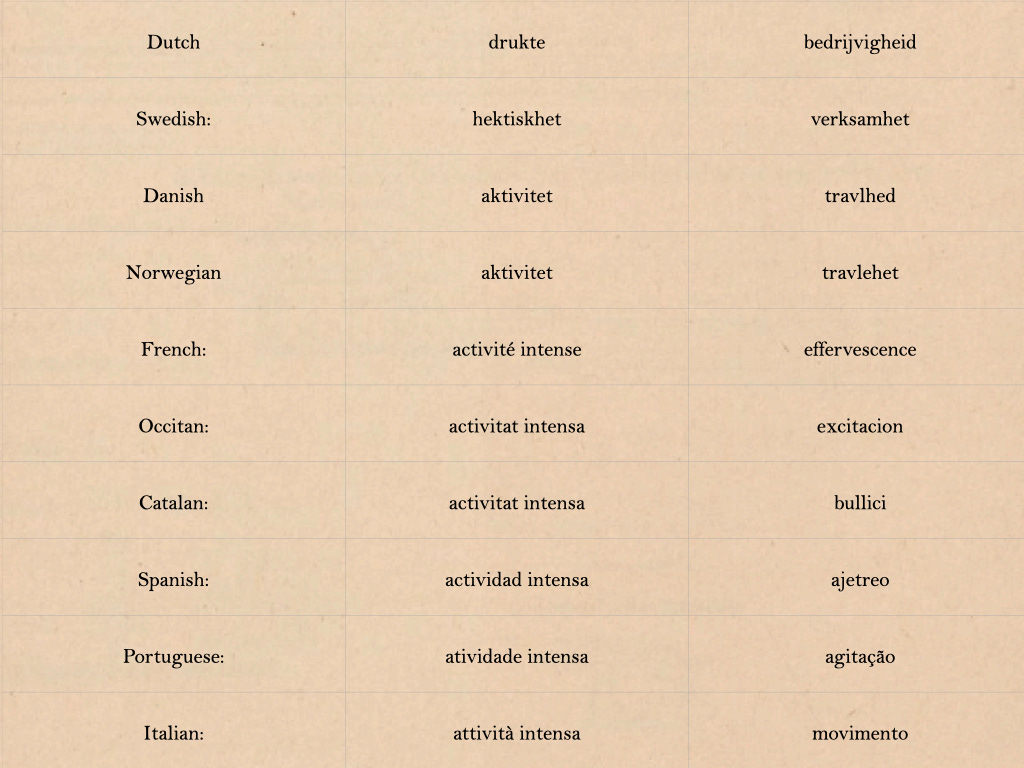

To provide this exercise with a proper finale, I asked Chat GPT to provide me with two translations of the German original into a number of different languages.

Alas, the word herd that resulted proved disappointing, to the point where I suspect that, rather than performing the task I had given it, Chat GPT was “translating translations.”1 That is, it used Google Translate to render Gehäftigkeit into English and, having found vehemence, converted the latter word into its equivalents in the ten languages on my list.

In conclusion, this little experiment taught me three things. Firstly, I was wise to begin with Hathi. Secondly, I could have gone directly to old dictionaries. Thirdly, Chat GPT lies like a cheap toupee.

For Further Reading:

If you would like to have some fun with that phenomenon, I recommend the Twisted Translations of Melinda Kathleen Reese. (The link will take you to the YouTube channel of Miss Reese.)

May be of interest on the failings of AI:

https://open.substack.com/pub/tedgioia/p/ugly-numbers-from-microsoft-and-chatgpt/

Don't you just love the way words never quite translate the same way twice?

In my use of GTranslate for my novel, I put in the term Bondswoman. I got three possible translations. Nighean Triall - Slave Girl, Bean Cheangail - concubine, or bean-bainnse - wife, or one that read tie-wife.

I've found out that words don't convey the spirit of what you want, so sometimes you have to describe the intent.

As always translation is a bugger.