Discover more from Extra Muros

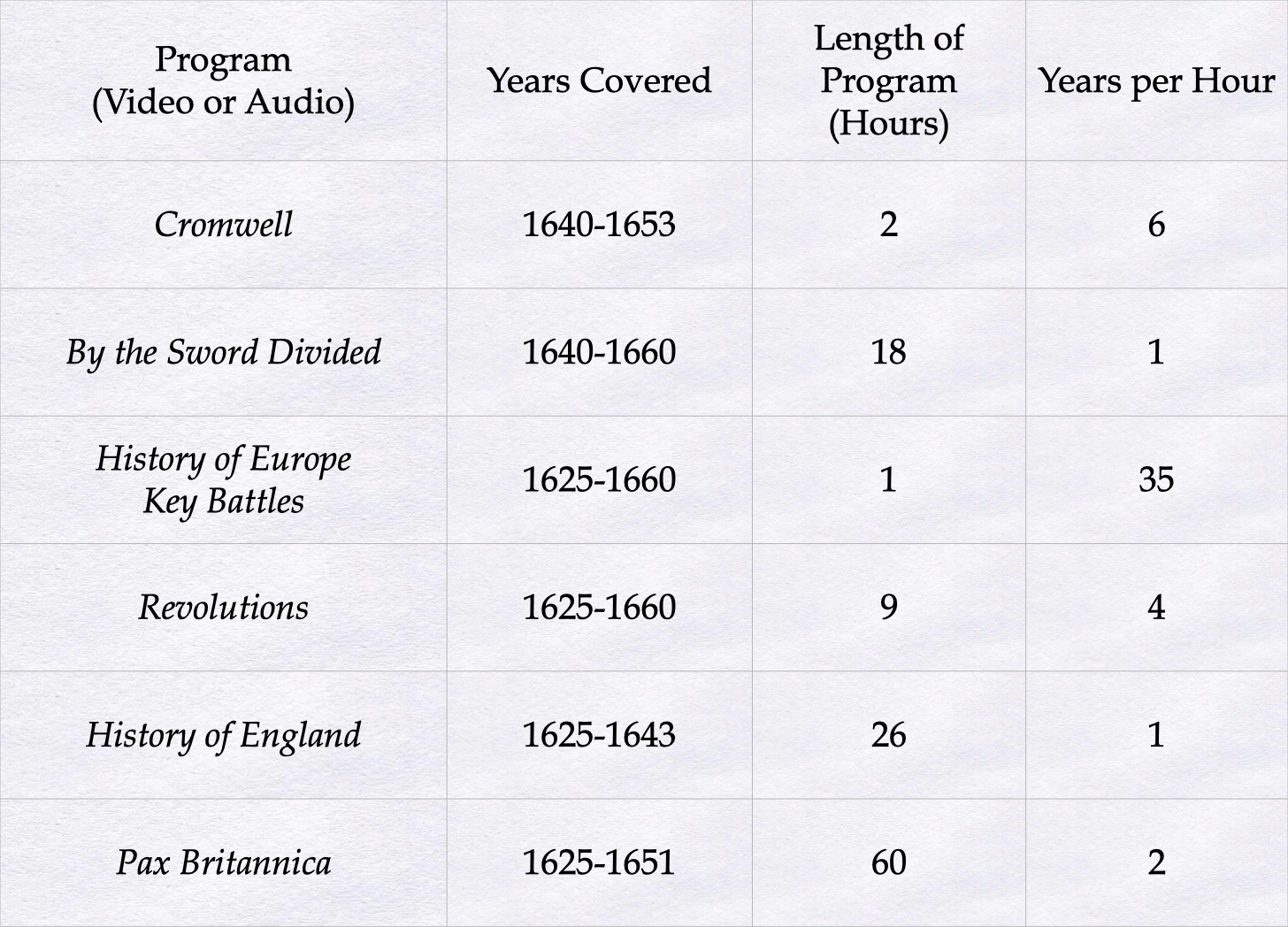

My interest in the first (and, so far, only) English republic owes much to Cromwell. Featuring both Richard Harris (in the title role) and Alec Guinness, this film tells the tale of the parliamentary back-bencher who, over the course of thirteen very full years, played a key role in both the establishment of the aforementioned experiment in kinglessness and its transformation into a military dictatorship.

Like so many period pieces, Cromwell sometimes takes liberties with the facts. Moreover, the depiction of the main characters, as well as the ideas, issues, and interests at play, borders on the melodramatic. (William Shatner, please call your answering service.) Nonetheless, the broad-brush (and, at times, over-the-top) treatment of the events, ideas, and personalities at play provides the stark contrasts that make for a solid introduction to a world much different from our own.

By the Sword Divided benefits from a similar degree of simplification. Made for the small screen in the days of Dynasty, this fictional family saga looks at the rise and fall of the aforementioned republic through the eyes of a young woman with strong ties to both of the two contending camps. Indeed, as the story extends over twenty one-hour episodes, many newcomers to the seventeenth century will prefer it to the aforementioned film, which attempts to describe the first half of the aforementioned period in a little more than two hours.

Taken together, two episodes from A History of Europe, Key Battles provide an audio analog to Cromwell.1 In fact, as this pair of podcast programs covers twice as many years in half as many hours, it might well be described as “four times as Cromwellian” as the eponymous film. Thus, Build Up to the English Civil War and The English Civil War provide both a good place to begin engagement with the brief-but-busy English republic and, for those who have already watched By the Sword Divided, a handy review of the main issues and events.2

Readers wishing to dive more deeply into the subject at hand will benefit greatly from the twenty-episode series of audio programs with which Mike Duncan began the Revolutions podcast. As might be expected from Mr. Duncan, who had previously made podcasting history with The History of Rome, this series provides lots of accessible explanations for the many complex phenomena at hand.

Finally, people interested in the listening equivalent of a lengthy underwater descent in the company of Jacques Cousteau will be delighted to learn that two splendidly accomplished podcasters have embarked upon extravagantly detailed treatments of the issues, events, and personalities of the years between 1625 and 1660. David Crowther has devoted thirty-four forty-five minute episodes of his magisterial History of England to the first half of this period. Not to be outdone, Samuel Hume of Pax Britannica, has employed a hundred slightly shorter instalments to cover nine-tenths of this era.

The sequence of programs laid out in this post moves from simple to complex and, with the exception of the television series, from short to long. It thus forms a progression, corresponding to the lectures of three semester-long undergraduate courses, that an ambitious autodidact might want to follow. (Once Messrs. Crowther and Hume have finished their series, the whole shebang will weigh-in as the rough equivalent of four courses.)

Readers may wonder why, in discussing these resources, I neglected to mention any books. This omission, quite simply, reflects my experience. Though I first saw Cromwell as a child and read a book on the subject of Charles I in my teens, my interest in the English Civil War and the short-lived Commonwealth that followed lay dormant for decades, until, thanks to the aforementioned podcasts, it awoke from its slumber.

Some may also ask why I failed to include To Kill a King in my list of recommended resources. The answer lies, I fear, in the great gulf that separates many (if not most) of the incidents portrayed in the film and my understanding of the historical record. That is, in contrast to a made up story set against the background of real events, To Kill a King falsifies both the actions of prominent figures (such as Oliver Cromwell and Lord Thomas Fairfax) and important facts about their lives.

The presenter’s custom of introducing, punctuating, and concluding each program with a well-chosen piece of era-appropriate classical music does much to enhance my enjoyment of A History of Europe, Key Battles.

Readers less interested than I in the finer points of enfilade and defilade will be relieved to know that, notwithstanding its martial subtitle, A History of Europe, Key Battles pays as much attention to matters of culture, politics, society, religion, and personality as it does to things that go “boom.”

Subscribe to Extra Muros

Extra Muros explores ways people can obtain the benefits of higher education while remaining "outside the walls" of our dying universities.

I’m just about finished reading Jonathan Healy’s new book “The Blazing World, a new history of revolutionary England, 1603 to 1689.” I don’t have much background with which to fully assess the book but that I can say it is wide-ranging and seems to reflect some serious research and reading. I was really pleased to realize how much this book might serve as good background to Bernard Bailyn’s “the ideological origins of the American revolution”. The that’s a long way of saying I really recommend it to others and would love to hear if anyone has some opinions on it.

Great stuff, many thanks, I know very little about this period.