Discover more from Extra Muros

In days of yore, when visiting an archive required long journeys by sea, or, at the very least, a tiring trek o’er moor and mountain, considerate historians stuffed their works, with extensive excerpts from primary sources.1 Later, when trains, planes, and automobiles made it easier for people to visit the places where original documents could be found, these quotations shrank, eventually to the point where the word ‘citation’, which had once described the products of scholarly stenography, came to designate the label that enabled readers to locate the one-of-a-kind text in question.

No doubt, this development saved many trees from the woodman’s axe. At the same time, however, it changed the role played by historians. Rather than showcasing selections from the correspondence of old-timey movers and shakers, Clio’s children devoted most of the ink that they spilled to the explanation of texts that, despite the blessings bestowed by coal and petroleum, most readers would not be able to read.

Many a noble soul resisted the temptation to sacrifice verbatim reproduction on the altar of erudite interpretation. Realizing that readers might prefer a faithful facsimile of the real McCoy to a ponderous paraphrase, these saints of the scriptorium prepared primary sources for the press. However, rather rewarding these benefactors of the historically curious with condign praise, the denizens of the faculty lounge often dismissed them as ‘editors’ and, in moments of especial cruelty, ‘antiquarians’.

In the fullness of time, the convenience provided by recent interpretations led many historians to prefer them to the relics of bygone bureaucracies. After all, reading a fresh-smelling, neatly-bound, clearly-printed, recently-written book asks less of a scholar than the deciphering of unfamiliar turns-of-phrase scribbled on the dusty, mite-bitten contents of cardboard boxes. Moreover, while the reader of a scholarly monograph often enjoys a wide choice of restaurants and coffee shops, and, at the very least, the delights of his own kitchen, the archival archeologist must often make do with the decidedly institutional offerings of a ground-floor cafeteria.

Ostentatious reliance on recent interpretations also enables a scholar to exhibit his collegiality. ‘See’, the favorable footnote screams, ‘someone noticed your work and, marvelous to say, made use of it’. Conversely, failure to cite the work of a peer, let alone a scholar of superior standing, signals a degree of nonchalance bordering on contempt. ‘I am fully aware,’ it says to the author of the unreferenced work, ‘that you poured your heart and soul, as well as a dozen years of your life, into your study, but I could not be bothered to type out its title, let alone turn a page to discover its date of publication’.

Finally, the making of new monographs out of the pieces of slightly older ones honors the founding fable of the research university, the myth of scholarly progress. The monograph still warm from the press, we presume, offers more in the way of insight and understanding than one that has been sitting on the shelf for decades. (If you wish to drive a dagger into the heart of an older academic, describe one of his earlier works, especially one that once made a splash in the kiddie-pool of his subfield, as ‘somewhat dated’.)2

Prejudice in favor of up-to-date interpretations creates a paradox. Historians, who exist to bring the past to life, favor interpretations created on the eve of now. The speakers for the dead (hat tip to Orson Scott Card) limit themselves to the thoughts of the living.

Of late, however, digital developments pose a powerful challenge to this way of doing business. Faced with a shortage of storage space, archivists and librarians have begun to digitize their holdings and, better yet, make them available online. Thus, rather than relying upon the overpriced précis of an earlier synopsis of an older abstract, any reader with access to the internet can go straight to the source. Better yet, he can use a wide variety of tools, whether machine translators or graphics programs, to make sense of what he finds. Best of all, when lunchtime comes around, the reader who engages old-timey writings in the form of PDF files will, in all likelihood, enjoy a number of tastier alternatives to LARPing as a diner in the canteen of a Soviet tractor factory.

In my own corner of Clio’s realm, the archival service of the German Federal Republic leads the pack in the race to digitize governmental records. With a view towards a future of broader broadband and cheaper hard drives, the folks at the Bundesarchiv who take digital pictures of old letters set the resolution on their scanners in ways that preserve an extraordinary degree of detail. In keeping with the same spirit of verisimilitude, they also make copies of the back sides of documents, even when, as is often the case, they seem to offer nothing more than a faint mirror-image of the text in question.

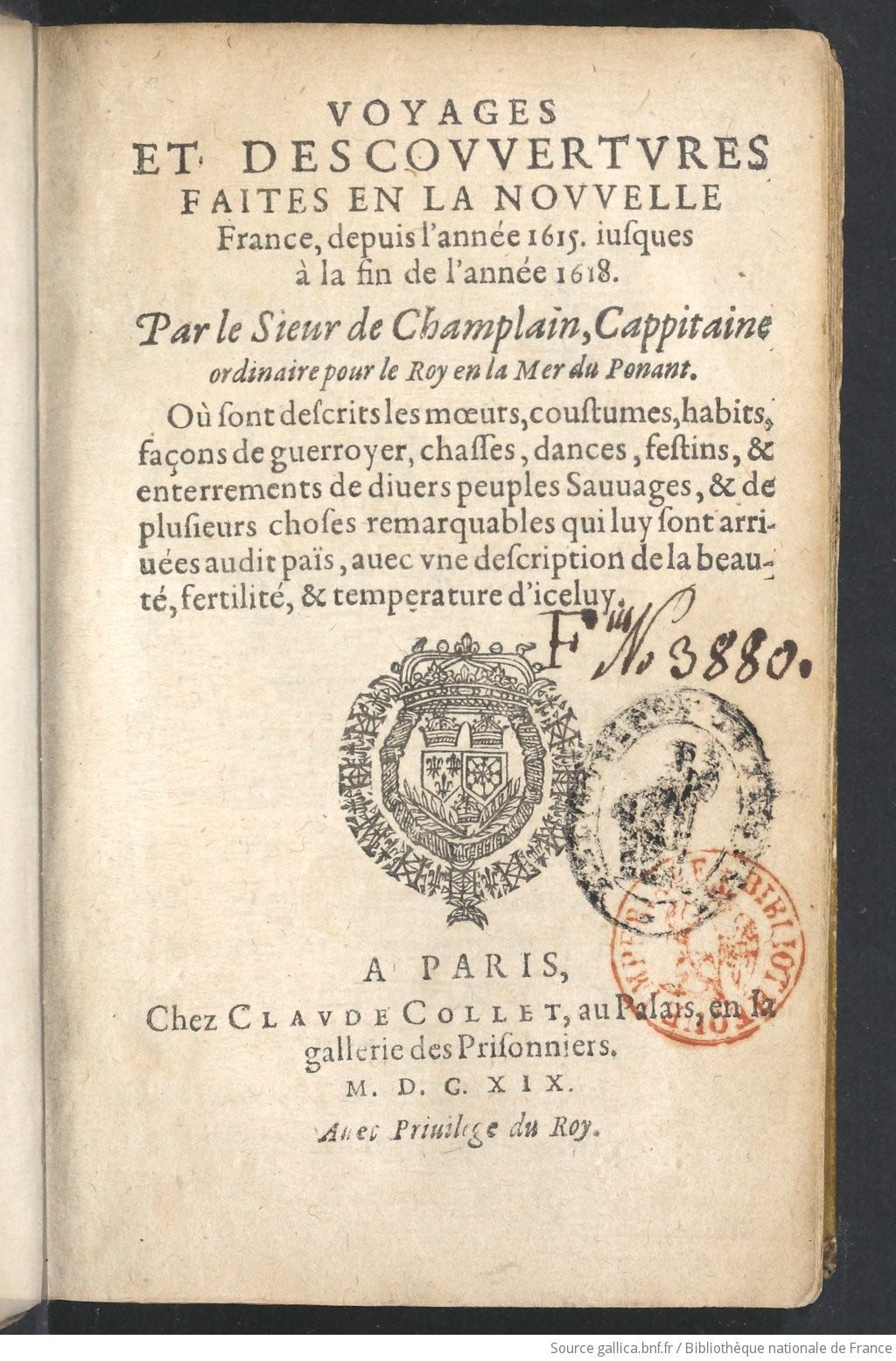

In much the same way, when it comes to the digitization of books, magazines, and other products of the press, first prize goes to the digital branch of the French National Library. Also known, at least in the idiolect of my atélier, as ‘Google Books done right’, Gallica offers high-quality electronic copies of materials that, under French copyright law, have passed into the public domain. Thus, without changing out of my pajamas, I am able to consult works that, not too long ago, could only be found in the rare book rooms of ludicrously large research libraries.

Not to be outdone by their neighbors on the west side of the Rhine, several German analogs of Gallica also do a fine job of digitizing older books. Of these, my favorite, by far, is the Digitale Bibliothek of the Munich Digitalization Center. (While it contains few works published after 1900, this library holds a dragon’s hoard of older items. As might be expected, most of these are written in German. However, thanks to the full-text track included with each PDF, readers can easily make machine translations of material that would otherwise elude them.)

Because of these resources, locating a PDF of a primary source, whether printed or archival, is often much easier than tracking down a copy of a recently published monograph. Moreover, given the outrageous prices that academic publishers charge for scholarly works, the distances that separate readers from the libraries open to them, and the unavoidable delays in securing a book by interlibrary loan, such consultation will often save the reader a great deal of time, trouble, and treasure.

That said, I will be the first to admit that online libraries suffer from serious gaps. Printed works published in the last century or so languish in waiting rooms of digital libraries until the date of their escape from the bonds of copyright. (In the United States, this happens on the 1st of January of the year a book or article turns 95. In France, the liberation of a work occurs on the 70th anniversary of the author’s death.) Nonetheless, only the most favored of the brick-and-mortar libraries harbor comparative collections of older works.

In much the same way, the offerings of digital archives pale in comparison to those of their analog antecedents. This gap owes much to the cost of scanning, storing, and sharing digital documents. It also reflects the desire of archivists to curate the materials they make available to members of the general population. (I suspect that archivists at the Bundesarchiv take especial care lest the fruit of their hi-res scanners buttress the arguments of a latter-day David Irving.)3

The widespread availability of digitized sources will not, by itself, deprive interpretation of all of its utility. After all, readers may still need a bit of help when it comes to making sense of materials written in times and places strange to them. Thus, to use an example that has lately been on my mind, readers of William Bradford’s History of Plymouth Plantation, will need reminders that the author (who died in 1657) lived in a time before the Pilgrims became known by that name, ‘plantation’ implied the presence of magnolias, and the word ‘savage’ acquired its present-day meaning of ‘cruel and bloodthirsty’.

That said, the sort of services that historians can provide to readers in the epoch of the PDF differ considerably from those that we offered in the analog age. For one thing, the products of our pens will, in many cases, be far less voluminous than they used to be. Some, indeed, may be no longer than a Substack post.

For Further Reading:

For a brief, and delightfully documented, description of the work of the paragon of this approach to the writing of history, Angelo Fabroni (1732-1803), see Anthony Grafton The Footnote: A Curious History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997) pages 82 and 83

Ask me how I know!

A German archive (or library) will often possess a Giftschrank, a ‘poison closet’ that holds materials that may only be consulted by persons who have received special permission.

Subscribe to Extra Muros

Extra Muros explores ways people can obtain the benefits of higher education while remaining "outside the walls" of our dying universities.

There is always, and especially as of late, a huge danger in “new interpretations” of older works as popular trends and changing political views can interfere with actual scholarship. Therefore the advent of widely accessible original material is truly a wonderful thing! This really facilitates research, not to mention fact checking, by nearly anyone.

With respect to footnote 2, OK, I will ask you how you know.

I hope you won't object to me quoting the first few paragraphs on my blog, and I especially hope you'll forgive me for the meme I used as an eyecatcher illustration to go with it!