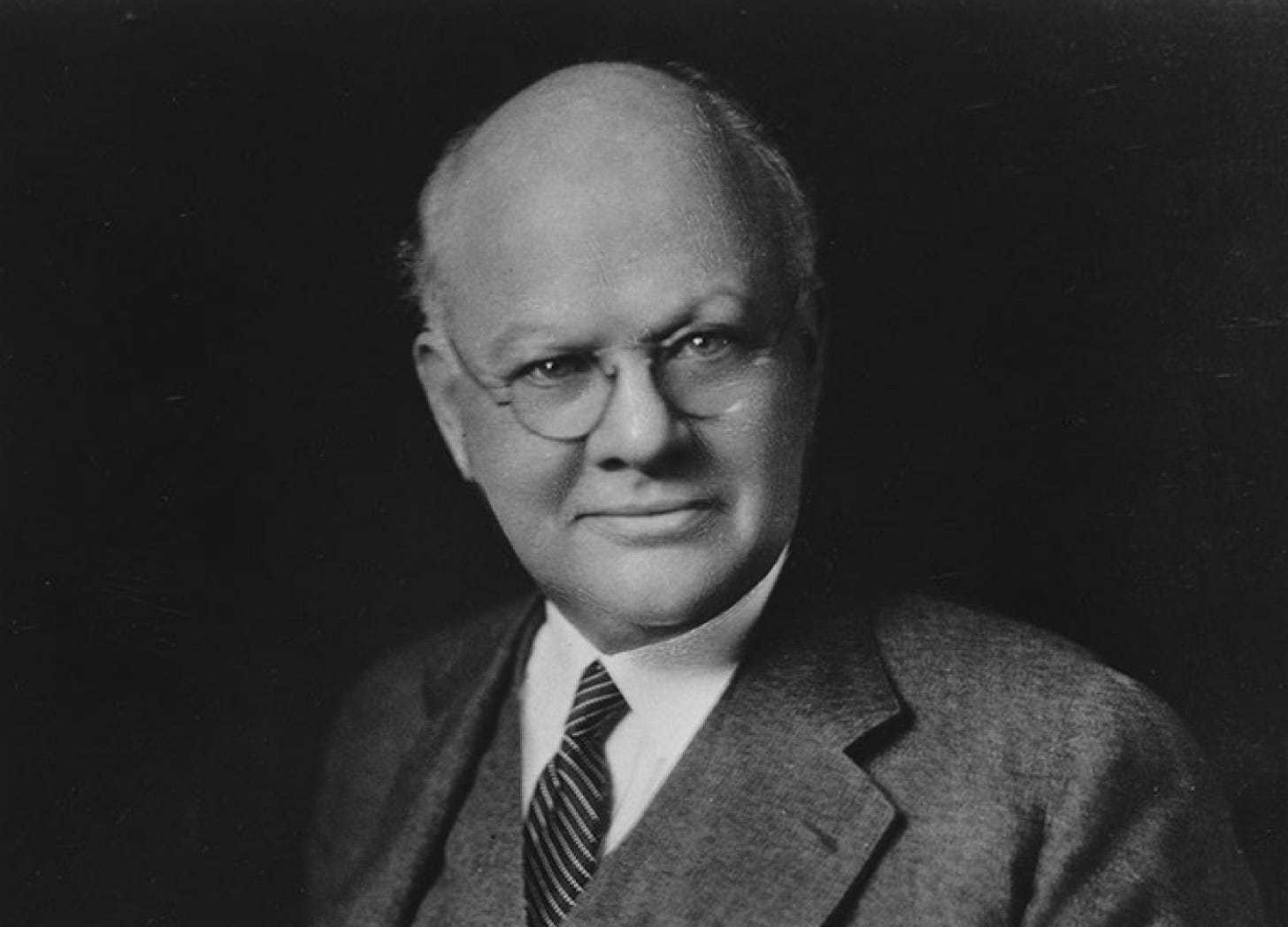

In 1944, the Harvard University Press published a slim volume that, marvelous to say, challenged the direction that Harvard University had been traveling since the latter years of the nineteenth century. Written by Wallace Brett Donham, who had served as dean of the Harvard Business School for twenty-three years, Education for Responsible Living argued that many (if not most) undergraduate colleges in the United States had become, in effect, tributaries of academic graduate schools.

“Indeed,” Donham wrote, '“the dividing lines between the college and graduate schools - except in discipline and athletics - became more and more blurred, to the disadvantage of the college. Many courses designed for specialized graduate students were opened to undergraduates, who were thus tempted to early specialization.”

“Under the impact of specialization in the graduate schools,” Donham added, “new specialities and new beginning courses multiply in the colleges. In the multiplication they become narrower in scope and less adapted to the needs of men seeking general understanding.” This, he concluded, led to a situation in which “teaching is often subordinated to research, to productive scholarship, and to publication.”1

The solution that Dean Donham offered to this problem owed much to the case method, an approach to learning that, in the early 1920s, he introduced to the Harvard Business School. Inspired by the technique of the same name that he had encountered while studying at the Harvard Law School, the case method made use of decision-forcing cases, exercises that place students in the shoes of real people who, at some point in the past, found themselves face-to-face with particularly challenging problems.

Drawn from a wider range of fields of human endeavor than the exercises used at professional schools, the cases that Donham would ask undergraduates to engage would provide them with “intimate concrete knowledge of human beings” as they “adapt themselves to changing environments.” In other words, rather than offering, as courses in the social sciences often do, conclusions about human behavior, these problems would allow them to accumulate a stock of working hypotheses that might prove useful in particular situations.2

Marvelous to say, Donham makes no mention of the use of decision-forcing cases at the US Army Infantry School in the 1930s. (Championed by George C. Marshall, who had since attained fame as chief of staff of the US Army, these “historical map problems” bore a close resemblance to the exercises that he seems to have had in mind.) What is less surprising in a book published during the Second World War, Donham declines to link his own concept of “education for responsible living” with the German tradition of using decision-forcing exercises to foster the “joy in taking responsibility” [Verantwortungsfreudigkeit] of military leaders.

The three quotations that precede the citation for this note come from Wallace Brett Donham Education for Responsible Living: The Opportunity for Liberal Arts Colleges (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1944) pages 38-40

Donham op. cit. pages 256-257

I am curious as to how Wallace would respond to today's universities/colleges. What advice would he have for the youth wanting a higher education?

The "Joy in taking responsilibity" was one of the reason why we had the best soldiers between 1870 (or even earlier) and 1945. They had their orders but could easily substitute leaders because even the regular soldier was schooled in taking over the responsilibities.

The funny think is that older generations from my family never said anything negative about school if they graduated before the 1970ies. When I went to school in the 90ies it sucked for everyone involved (teachers and pupils). Did we loose the joy of responsilibity in the meantime?