French people cry a lot. Not in the sense of weeping, mind you, but in the sense of ‘cry havoc, and let slip the dogs of war’. 1

All this vociferation has spawned a minor myriad of clamorous expressions, each of which combines cri de [‘cry of’] with a narrowing noun. Thus we are able to say …

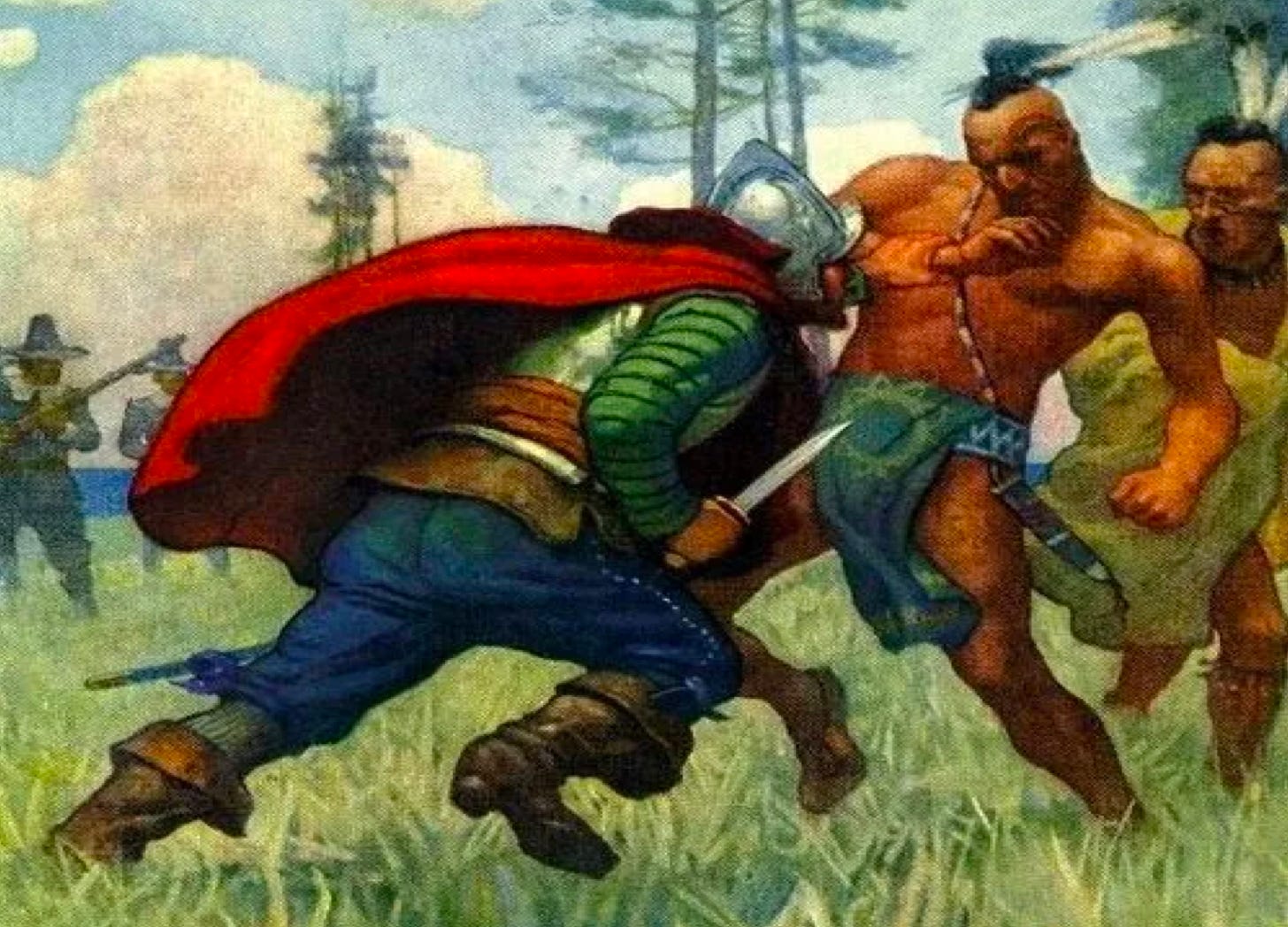

Pecksuot, of the Massachusetts people, promoted his project for Pilgrim remigration with the cri de ralliement of ‘Make Algonquins Great Again’. Alas for this enterprise, Miles Standish learned of the plot, raised a cri d’alarme, and ambushed the Native nativist. The last words of the waylaid warrior - ‘Yankee go home’ - struck some observers as a cri de rage. Others, however, took them as a cri de désespoir.

Of the many cri de constructions coined in the Francophone world, speakers of English enjoy the greatest degree of familiarity with cri de cœur. Thus we have the case of celebrated suffragette May Sinclair who, in her appreciation of les sœurs Brontë, employs this French rendering of ‘cry of the heart’ on no fewer than three separate occasions.2

Extraordinary that Charlotte's critics have missed the pathos of that cri de cœur. It is so clearly an echo from the 'house of bondage', where Charlotte was made a stranger to the beloved, where the beloved threw stones and Bibles at her.The great orchard scene does not ring entirely true. For pages and pages it falters between passion and melodrama; between rhetoric and the cri de cœur.In her great scenes she is inspired one moment, and the next positively handicapped by her passion and her poetry. In the same sentence she rises to the sudden poignant cri de cœur, and sinks to the artifice of metaphor.Second prize - and a distant one at that - goes to cri de joie.

The reason for this distance, I suppose, owes much to the presumption that things said in French ought to reflect a certain sadness, and, in particular, sadness of an especially sophisticated sort. Pathetic, melodramatic, and poignant, cri de cœur partakes of this prejudice. A simple, straightforward, and unapologetically optimistic ‘cry of joy’ does not.

To put things another way, French is the language of Edith Piaf, Jacques Brel, and Pierre Loti, English that of Marie Osmond, Bobby McFerrin, and Norman Vincent Peale.

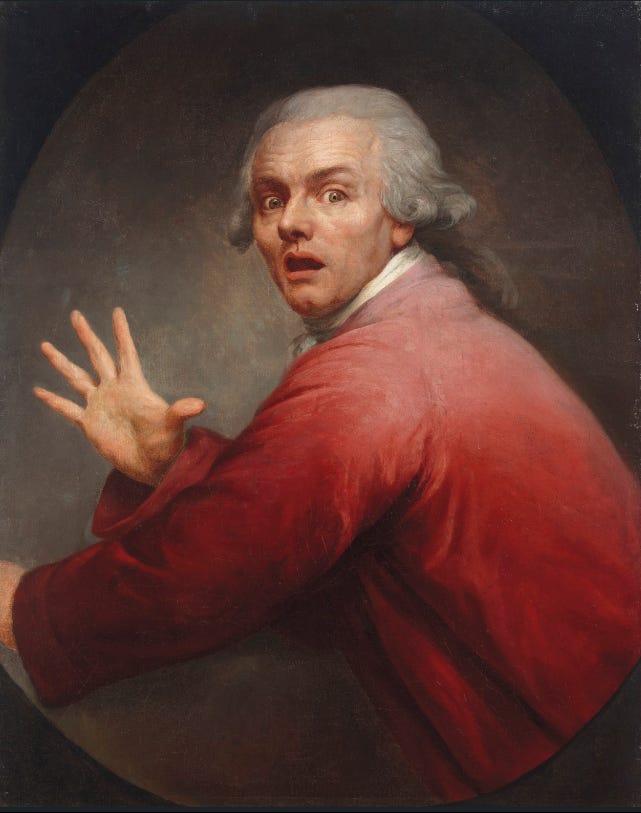

At this point in this wee screed, you may wonder at how I’m going to make a suitable segue into the part of the piece that talks about the word rivière. Alas, the best I can do is point out the adumbration provided by the painting at the top of the page, the work of the doyen of Victorian dog-depicters, Briton Rivière.

Old-timey French people used rivière in much the same way that their English-speaking contemporaries used ‘river’. Indeed, if I am not too badly mistaken, the latter word owes its existence to the former.

A little more than two centuries ago, when the bonhommes of Paris were being Bolshie avant la lettre, the significance shifted. Thus, rather than referring to the watery stream, rivière came to mean the banks along which the wet stuff flowed. (To describe the latter, Latin lovers turned fluvius - as in ‘effluvium’, ‘effluent’, and ‘fluvial’ - into fleuve.)

As with so many relics of the ancien régime, the original meaning of rivière lives on in Quebec. (Once, while I was enjoying a promenade on the streets of Montréal, a gentleman of the mendicant persuasion began his request for a condign contribution to his recreational fund by addressing me as monseigneur. I was so taken aback by the anachronism of this encounter that I almost lost my powdered wig.)3

For Further Reading:

For a delightful (and delightfully indie) film that revives this Shakespearean phrase, take a look at The Gamers: Hands of Fate.

May Sinclair (pseudonym of Mary Amelia St. Clair) The Three Brontës (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), pages 65, 124, and 128.

Save for the bit about the wig, this tale is true.

One prominent city in Quebec is Trois Rivieres, called that for obvious reasons.