"Lectures were once useful ; but now, when all can read, and Books are so numerous, Lectures are unnecessary. If your attention fails, and you miss a part of the Lecture, it is lost. You cannot go back as you can upon a Book."

Samuel Johnson1

In the Middle Ages, books were hard to come by. Indeed, they were so scarce that students at universities would often pay the owner of a book to read parts of it aloud while they took notes on wax-covered tablets. As many could write while the “lecturer” (from the Latin for “reader”) read, such “lectures” (“readings”) took less out of a student’s purse than the hiring of the tome in question. The same economy of scale also allowed the reader to make a better return on his capital than he would get from running a single-volume rent-a-center.

As might be expected, the widespread availability of printed books (hat tip to Meister Gutenberg and Meester Coster) put the original gangsters of the lecture racket out of a job. Soon thereafter, the words used to describe the viva voce vocalists and the thing they did found themselves on Linked In, “open to new possibilities.”

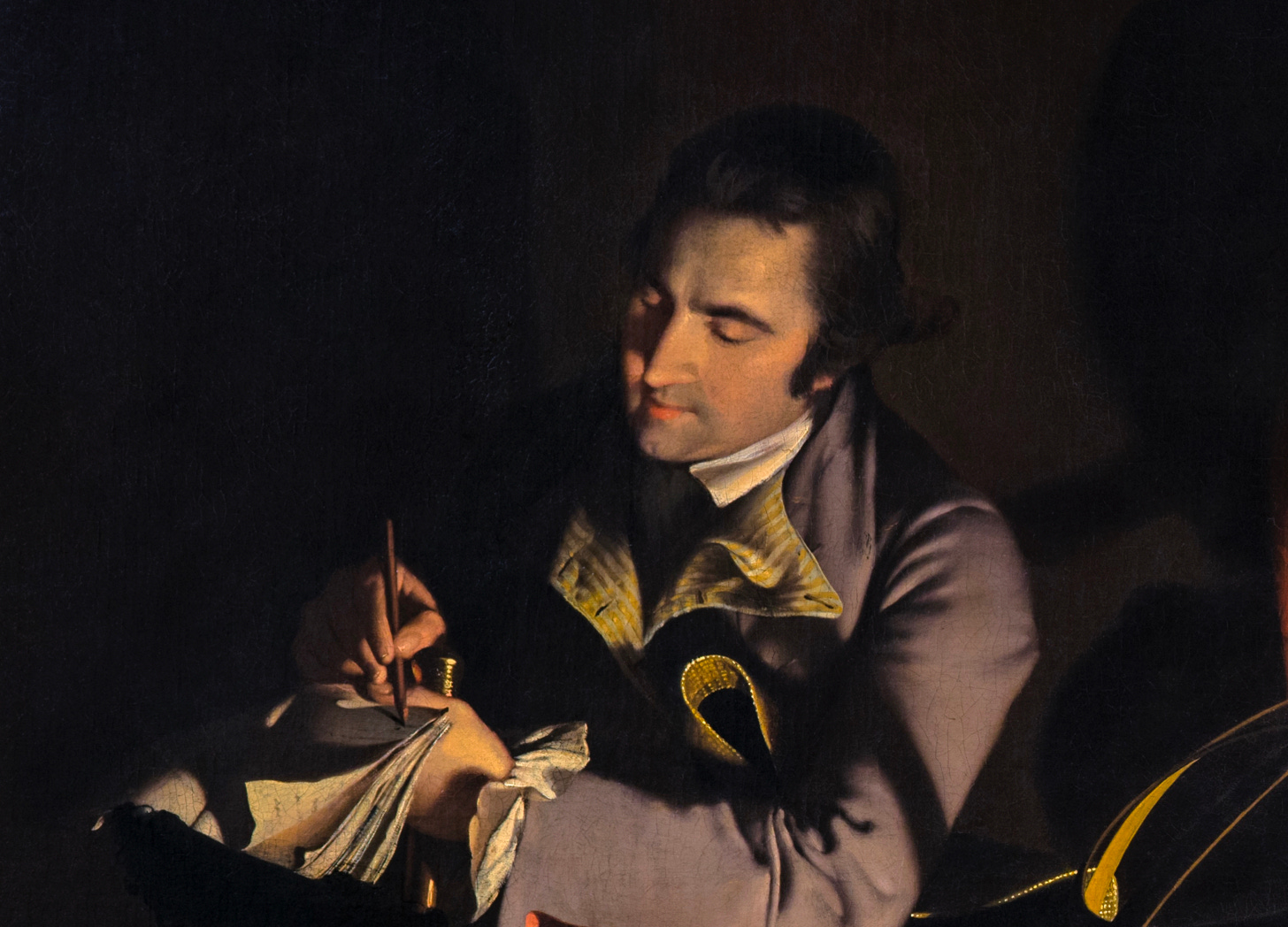

History failed to record the fate of the voice actors avant la lettre. “Lecture,” however, found work in the English-speaking world as a substitute for “oration.” Thus, even though he spoke words of his own composition, a market-day Demosthenes of the age of big buckles on hats and shoes was said to “lecture.” Indeed, the distance from the original meaning of the term had grown so great that speaking from notes, let alone reading from a text, had become the mark of a second-rate “lecturer.”

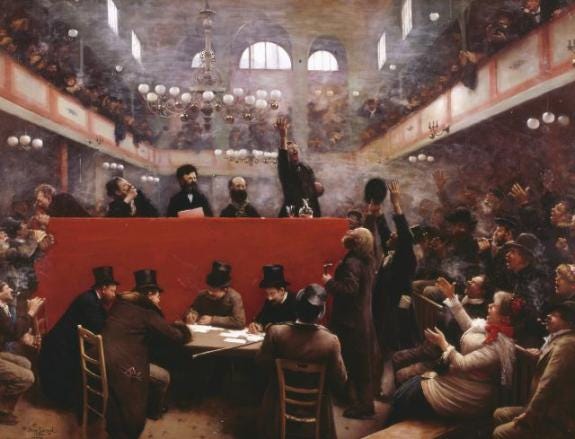

As shoe buckles shrank and folk began to fold their hats, lecturers and their listeners moved indoors As before, the former offered, and the latter demanded, a high degree of originality. Thus, even when (as was increasingly the case), the audience included large numbers of students and the speaker bore a title bestowed by academic authority, the lecture had more to do with the unveiling of new knowledge than the transmission of old wisdom.

Much of the material presented in lectures of this sort would eventually find its way into books.2 In many cases, however, several years would pass between the expression of an idea viva voce and its debut between the covers of a book. Thus, for example, ideas that Adam Smith shared in 1763 in a series of public lectures did not appear in print until 1776, when The Wealth of Nations first emerged from the press.3 In other instances, the libretti of lectures languished in cupboards for decades as their authors, such as the prolific polymath Immanuel Kant, shifted their attention to other projects.4

The gap between spoken speech and printed text led many listeners to take notes and, quite often, to attempt the verbatim transcription of the words they heard. Though sometimes used for nefarious purposes, such as piratical publication and blatant plagiarism, the products of such stenography seem, for the most part, to have provided listeners with information they would be hard pressed to find elsewhere.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, two developments conspired to change the character of public lectures. One was the proliferation of less scholarly forms of oratory, such as the political speech and the humorous monologue. (In other words, William Jennings Bryant and Mark Twain took the places previously occupied by Adam Smith and Immanuel Kant.) The other was the replacement, intra muros, of classical curricula, based on the study of classical languages and time-honored texts, with elective courses.

Elective courses owed their existence to the proposition that, rather than assisting students acquire a body of knowledge common to all educated people, the teacher used lectures to share particular insights into a specialized subject. In such a world, where “sages on stages” had displaced “guides on the side,” clever students quickly learned that notes taken in class provided a better guide to the questions asked on examinations than the books they had been told to read. (They also learned the great exception to this general rule, which occurred when the professor assigned one of his own books.)

No scholar, however, can be original about everything in his field. Thus, the lectures given in many classes contained a great deal of second-hand information. Indeed, in the course of the past century-and-a-half, as specialists have become more specialized, the amount of “filler material” in lectures has grown, to the point where much, if not most, of the content of lectures consists of whatever combinations of fact and fancy happened to be close at hand when they were composed.

Consider, if you will, the case of a course of lectures on the early Middle Ages given by Paul Freedman, a specialist in the history of food, the social history of Spain, and, in particular, the medieval spice trade. While the creation of this course gave Professor Freedman opportunities to season his lectures with occasional references to the objects of his studies, it required that he devote the lion’s share of each class to matters that had little to do with nutmeg and pepper. So, as professors have done for several generations, he filled his lectures with tales he found in books.5

Because of this, there is little in Freedman’s lectures that could not have been found, at any point in the last century, in a suburban public library. Thus, for example, he declines to mention, let alone address, the groundbreaking work done in the past few decades on the Arab conquest of the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain.6 To put things another way, the lectures Freedman serves up, while palatable and reasonably nutritious, cannot compete, whether for flavor or quality of ingredients, with many of podcasts that deal with the subjects he covers.

With those things in mind, there was no need for students inherently interested in the people, peoples, and events described in Freedman’s lectures to take notes. The fact that they did so suggests that their chief concern had less to do with Clovis, Childeric, or Charlemagne than with their belief that things mentioned in class stood a good chance of showing up on a test.

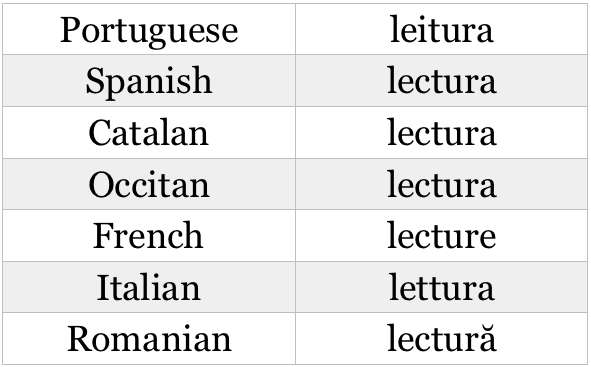

Readers can test this proposition by conducting searches, filtered by date of publication, on the word “lecture” in the online catalogs of large libraries. (To exclude books in French - or gallicized German - on the subject of reading, readers should limit results to books written in English.)

Willy Kaminski Über Immanuel Kants Schriften zur Physischen Geographie [On Immanuel Kant’s Writings About Physical Geography] (Königsberg: H. Jaeger, 1905)

Readers interested in an account of the Arab conquests that makes use of recent scholarship will find much of interest in Tom Holland The Shadow of the Sword (Boston: Little, Brown, 2012).

This article is inspiring. This article will even help me write an article myself. Thank you Extra Muros writing this.