Welcome to Extra Muros, where you will find many short articles on the subject of self-directed education. If you like what you see, please share this post with your friends. If you don’t, please send a copy to your enemies.

Logistics is the art of obtaining, storing, and moving things. In the world of commerce, the things in question are, well, things. In universities, however, the objects obtained, stored, and moved are stories that, like the myths of bygone days, attempt to explain some aspect of reality.

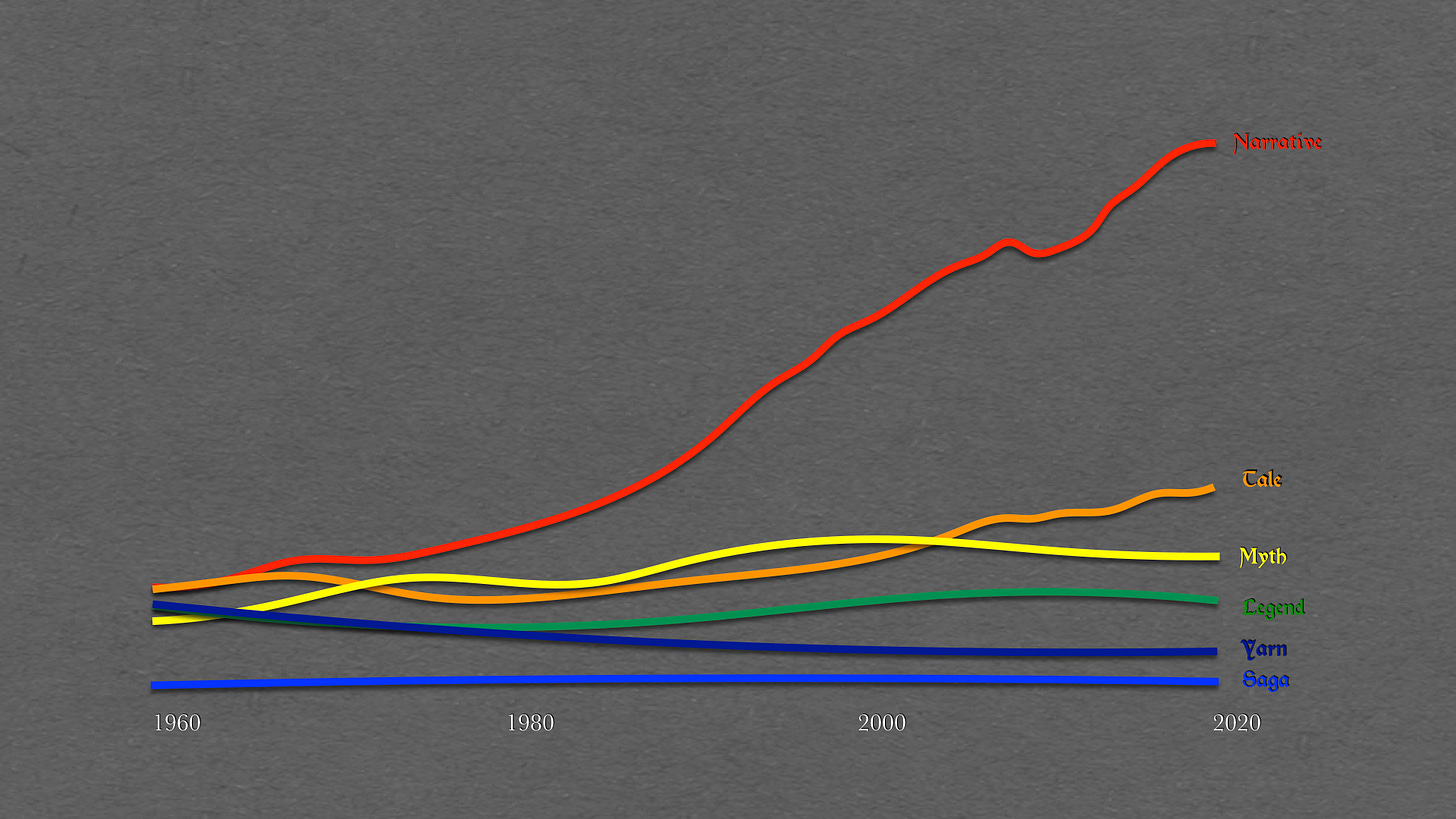

During the past six decades or so, folks of the professorial persuasion have come to describe these stories as ‘narratives’. Of course, they will take pains to explain that a ‘narrative’ is much more than a mere ‘story.’ This is particularly true of the narratologists who, mirabile dictu, practice the seriously serious science of narratology.

To a certain degree, the narrative mongers are right. Academic narratives have none of the things that make for a proper tale: neither plot, nor pathos, nor treasure-hoarding dragons. That said, academic narratives often feature heroes and villains, often to the point where they qualify as melodramas.

In ‘taught courses’, narratives play a central role in the textbooks students read, the lectures that they attend, and the essays that they write. To be more specific, while textbooks and lectures promulgate narratives, student essays, whether written at leisure or scribbled into little blue notebooks, give students opportunities to demonstrate their ability to replicate such stories.

At the level of the ‘terminal degree’ (how’s that for an ominous term of art?) doctoral candidates enjoy a slightly different relationship with the narratives of their respective fields. As they are being trained to serve as the keepers of a (surprisingly small) number of narratives, they do a lot more in the way of application. That is, they are obliged to find a new story, and tell it in a way that validates the the existing narrative of the tribe they wish to join.

Consider, if you will, the tale of the folk I like to call the Birminghamsters. Based out of the Centre for First World War Studies at the University of Birmingham, these scholars promote a narrative centered (centred?) on the notion of the “learning curve.” Rather than being the bunglers and butchers of popular imagination, they argue, the British generals who commanded on the Western Front were clever chaps who engaged in, or, at the very least, endorsed a great deal of innovation.

Birminghamsters studying for taught masters degree in First World War studies will read books, listen to lectures, engage in conversations, and write papers that support this narrative. Those who seek a doctoral degree will produce a substantial piece of writing on a previously unsung aspect of the “learning curve.”

There is, of course, some truth in this tale. It is certainly more credible than the narrative (there’s that word again) at the heart of “Black Adder Goes Forth.” (For more on that subject, please see the two wee books I wrote on the subject of the British Army of the First World War.)

That said, single minded focus on a well-bounded collection of characters and episodes, provides students with few opportunities to exercise their critical faculties. For one thing, challenging the central narrative of an academic program puts a student on the path to failure. For another, the ties that unite the various elements of a narrative are, from the point of view of logic, essentially arbitrary. (To put things another way, a narrative is not, in the strict sense of the word, a thesis.)

Trained in this way, university graduates have few means of evaluating the narratives they encounter later in life. Indeed, the greater the success they enjoyed in the classroom, the greater their ability to absorb, without too much in the way of thinking, the complicated stories that come their way.

This phenomenon explains the appeal of “climate change” to certain segments of the population. As an argument, climate change resembles a house of cards. That is, the falsification of any one of its component parts - that the net effect is a bad thing, that it is caused by people who do some things, that can stop it by doing other things, that it is happening at all - negates the entirety of the proposition. As a narrative, however, it bears a close resemblance to the many other stories that folk at universities absorb, replicate, and promulgate.