Entrée

Pardon My French

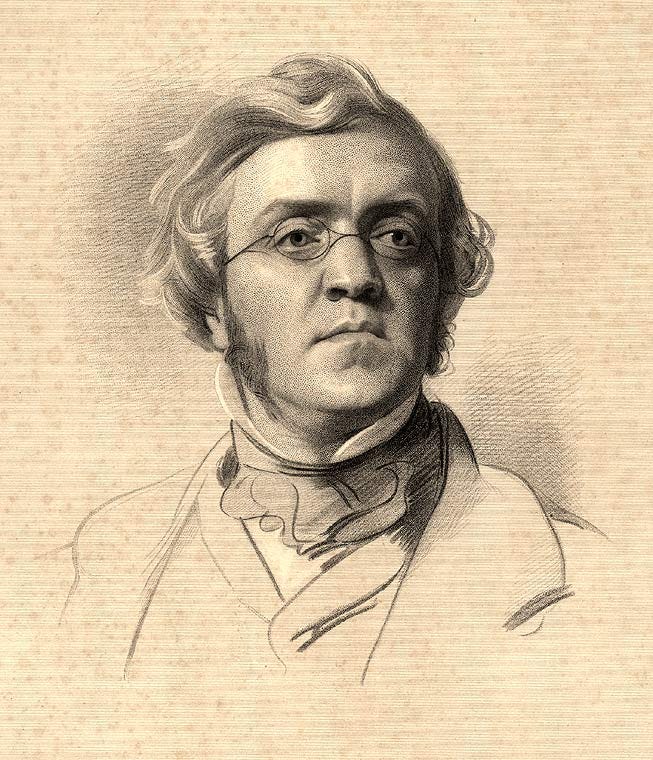

In A Little Dinner at Timmins’s, William Makepeace Thackeray used entrée to mean two different things.

The women had had a long debate, and something like a quarrel, it must be owned, over the bill of fare. Mrs. Gashleigh, who had lived a great part of her life in Devonshire, and kept house in great state there, was famous for making some dishes, without which, she thought, no dinner could be perfect. When she proposed her mock-turtle, and stewed pigeons, and gooseberry-cream, Rosa turned up her nose — a pretty little nose it was, by the way, and with a natural turn in that direction.

'Mock-turtle in June, Mamma!' said she.

'It was good enough for your grandfather, Rosa,’ the Mamma replied: 'it was good enough for the Lord High Admiral, when he was at Plymouth; it was good enough for the first men in the county, and relished by Lord Fortyskewer and Lord Rolls; Sir Lawrence Porker ate twice of it after Exeter races; and I think it might be good enough for ...’

'I will not have it, Mamma!' said Rosa, with a stamp of her foot; and Mrs. Gashleigh knew what resolution there was in that. Once, when she had tried to physic the baby, there had been a similar fight between them.

So Mrs. Gashleigh made out a menu, in which the soup was left with a dash – a melancholy vacuum; and in which the pigeons were certainly thrust in amongst the entrées; but Rosa determined they never should make an entrée at all into her dinner-party, but that she would have the dinner her own

way.

In the seventeen decades since Mr. Thackeray assembled this jeu de mots, one of these meanings has changed. The cooked dish that appeared right before the high point of a multi-stage meal – the prodigious piece of beef or mutton that Victorians called ‘the joint’ – has since moved to other parts of the gustatory workout. In the English-speaking parts of North America, entrée has come to describe the descendent of the aforementioned hunk o’ meat. Elsewhere in the Anglosphere, it often serves as a synonym for ‘starter’ or ‘appetizer’.

By the way, if you find yourself in Paris, with a rumbly in your tumbly, remember that a menu that refers to the main course of a meal as an entrée provides prima facie evidence of an attempt to appeal to transatlantic Anglo-Saxons. (The chalkboards of eateries that cater to people from other places will usually use plat to indicate dishes served on full-sized plates.)

In the same century-and-three-quarters, the other sense of entrée employed by Thackeray – which allowed it to be used instead of ‘entrance’ or ‘appearance’ – went the way of mutton-chop whiskers. In much the same way, the increasingly democratic manners of the twentieth century deprived the kissing cousin of that meaning, which had once provided people with another way of saying ‘formal introduction’, with much of the work it had once done.

In the 1930s, a prolific American author of ‘how to’ books tried to breath new life into the food-free version of entrée by changing the position of the person making his first appearance. No longer dependent on the sponsorship of an established insider, the debutant had become his own promoter.

‘The approach, the entree, the first contact. This is a special art in itself. Many salesmen have lost their sale before they have opened their mouths, because of a bad approach. It is highly strategic. Try to make an appointment by telephone, keep it promptly. Do not try trick dodges to make an entree.’Alas, this initiative fell afoul of another artifact of the Age of the Common Man, the increasingly popular use of entrée to dress up the meat-and-potatoes dish at the heart of a sit-down meal. Thus, rather than describing the most challenging part of their profession as ‘the special art’ of the ‘entree’, American salesmen adopted the simple, memorable, and chillingly accurate, ‘cold call’.

Sources for Passages

William Makepeace Thackeray The Memoirs of Mr. C. J. Yellowplush.

The Fitzboodle Papers. The Wolves and the Lamb. Stories and Sketches (Boston; Houghton, Mifflin and company, 1889) page 362

Justus George Frederick How to be a Convincing Talker and a Charming Conversationalist (New York: 1937) page 184