Over at Becoming Noble, Johann Kurtz argues that the willingness of women to bear children owes much to the social standing enjoyed by housewives. When activities that enhance status accord with motherhood, women embrace that vocation. When, however, the devotion of time, trouble, and treasure to the raising of children inhibit social advancement, women choose to do other things.

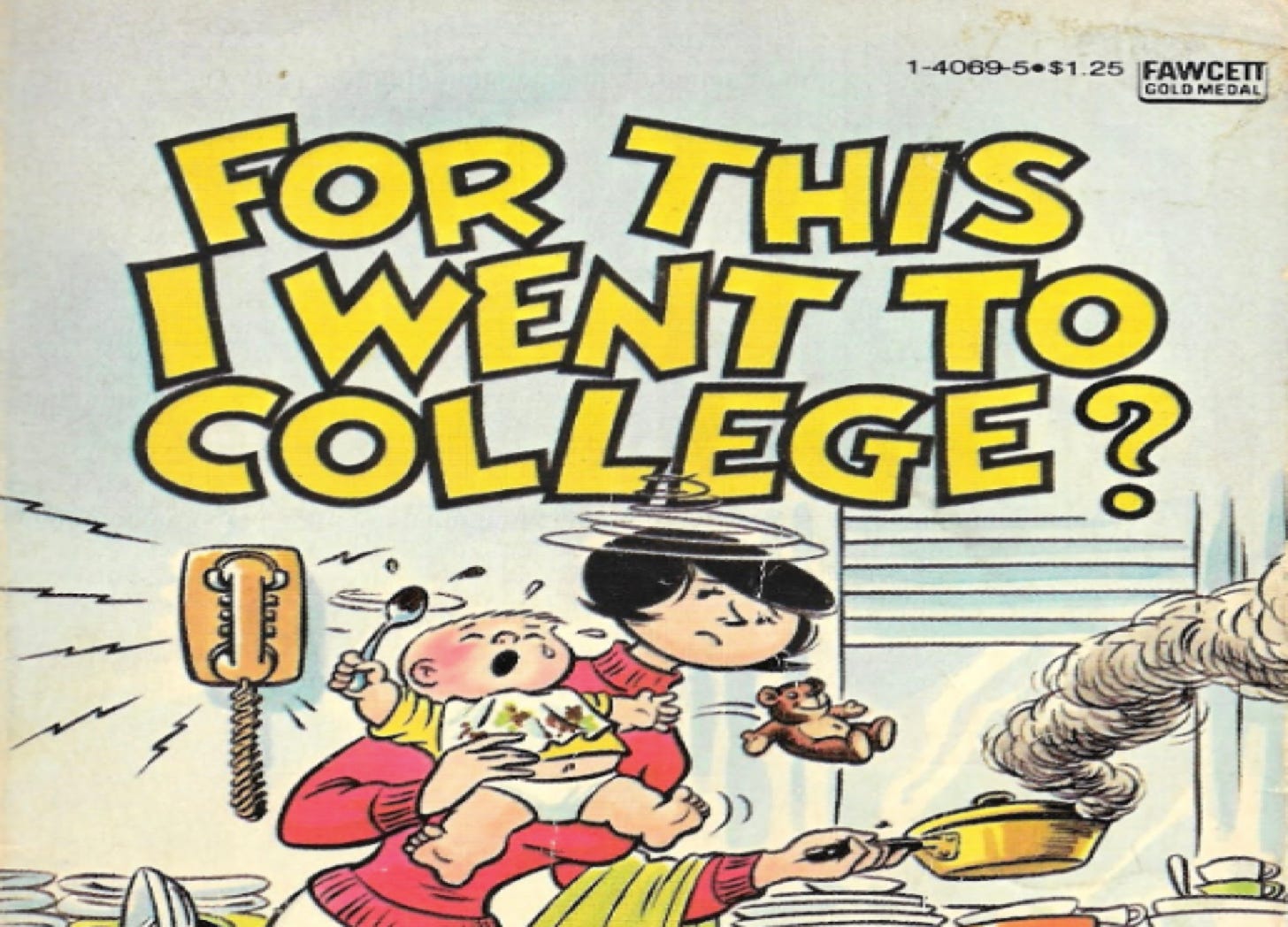

Reading the first article on this theme penned by Mr. Kurtz took me on a trip down memory lane. In particular, it brought to mind a rhetorical device I often saw in the early nineteen seventies. Found on posters, in the pages of Ms. magazine, and, marvelous to say, a panel from the Family Circus comic strip, this meme avant la lettre combined an image of a woman performing a menial task with the slogan ‘for this, I went to college?’ (Readers familiar with either New York Yiddish or Milwaukee Deutsch will appreciate the way that the reversal of subject and object enhanced the irony of the statement. It also suggests that the lady in question had embraced the reverse snobbery so much in evidence among recent college graduates of that time.)

‘For this, I went to college’ drew much of its power from the widespread assumption that attendance at a school for young adults would (or, at the very least, should) guarantee perpetual freedom from blue-collar work. Thus, the idea of a college graduate finding herself, mop in hand, cleaning up after persons of the puerile persuasion struck many as a violation of this promise, and thus a sort of secular sacrilege.

The meme also owed much to the three great developments that, over the course of the past century or so, had deprived housewifery of its managerial character. First, the lady of the house lost the services of the people, whether maids or milkmen, cooks or coal mongers, who had previously performed household tasks of the humbler sort. Second, changes in the way people bought, stored, and prepared comestibles reduced the need to devote foresight, detailed knowledge, and considerable creativity to the acquisition, storage, and preparation of food and drink. Third, the rise of schools that claimed to develop complete persons, and, in doing do devoured complete childhoods, led to the outsourcing of much of the education that, once upon a time, had taken place at home.

Consider, if you will, the case of my paternal grandmother, the mortal remains of whom rest beneath a headstone emblazoned with the word ‘housewife’. Born in the last decade of the nineteenth century, she married, and bore ten children to, the foreman of a gang of stevedores who worked on the docks of Reykjavik. (My surname, the patronymic of my father, preserves the memory of the latter’s Christian name.) In other words, my grandmother belonged to the higher rungs of what her Edwardian contemporaries called the ‘respectable working class’.

Notwithstanding her modest station in life, my grandmother employed a maid. Moreover, as her daughters grew in age and capability, she spent progressively less time doing domestic chores than planning, explaining, and supervising the execution of tasks, from washing clothes in a tub to cooking on a coal-fed iron stove, that were far more demanding than their present-day analogs. In short, while never afraid to get her hands dirty - her house, after all, was heated by coal and lit by kerosene - my grandmother exercised faculties similar to the ones her husband wielded at work.

In the century that followed, modernity, in the form of both machines and organization, increased the number of people who, in the world of work, needed to plan, explain, and supervise. At the same time, by eliminating the need for people to build fires, wash clothes by hand, and prepare all meals from scratch, the domestic counterparts of these novelties, from washing machines to supermarkets, reduced the managerial functions, and thus the status, of the housewife.

The great increase in formal schooling wrought a similar demotion. Once upon a time, home-based mothers did a great deal of teaching, both formal and informal. They taught cooking and sewing to their daughters, things like music, religion, and social dancing to children of both sexes, whether their own or those of their neighbors. Each time, however, such instruction passed into the hands of professionals, the housewife became less of a teacher, and more of a taxi driver. Moreover, as formal instruction necessarily takes place at established hours, the chauffeurs of persons too young to submit tax returns have become, like factory workers and employees in a fast-food restaurant, slaves to the clock.

In a world in which most Amish people own washing machines, few women will trade their Maytags for a tub and a scrub board, even if it came with a maid to do the scrubbing. Thus, the centerpiece of any campaign to restore the social standing of the full-time mother should be the promotion of home-based learning, and, more broadly, the cultivation of a culture of self-directed education.

To increase the status of the Housewife, one should also look to facilitating the creation of the social networks among women in the neighborhood. I recall in my youth the wives of the neighborhood all knew each other and cooperated closely. More than once I was told to 'run this sugar over to Mrs. Larsen' or when being sent to the store to get things we needed, I'd be told 'pick up some X at Fred Meyer and drop it on the way home at Mrs. X's house.' These women organized baby-sitting, large scale purchases to reduce unit cost of foodstuffs, etc. My mother's skill at cake decorating was prized; to get her to make a cake for an occasion was a Very Good Thing.

We are socially atomized. Put human beans in closer social proximity and the status of homemaking will increase. Now, women have only the internet/entertainment complex to compare their status to. That's a losing proposition. Give them a local arena of similar persons to compete for status among, and you will see a rise in the value of the homemaker.

While colored by my own very negative experience in the Empire State's public education system, my opinion of modern schooling has stemmed overwhelmingly from a very similar set of observations.

On the bright side, these schools are less and less popular by the day. I dont see the modern school system surviving the next century in its current form.